Xunpu 菌譜, also called Xiangxunpu 香蕈譜 or Xiangcaopu 香草譜, is a book on mushrooms written during the Southern Song period 南宋 (1127-1279) by Chen Renyu 陳仁玉 (fl. 1245), courtesy name Degong 德公 or Dehan 德翰, style Biqi 碧棲, from Taizhou 臺州, Zhejiang.

Chen obtained the jinshi degree in 1259 and was appointed concurrently department director of the Imperial Library (bishu lang 秘書郎) and in the Ministry of Rites (libu lang 禮部郎). Chen was later made judicial commissioner (tixing 提刑) of the circuit of Zhedong 浙東 and prefect (zhizhou 知州) of Quzhou 衢州. In 1260, he returned to the central administration as a documentary secretary in the Huawen Hall 華文閣 and the Fuwen Hall 敷文閣, and was then made surveillance commissioner (anchashi 安撫使) of Zhedong. He crowned his career with the post of Vice Minister of War (bingbu shilang 兵部侍郎). After 1276, he fought against the Mongols, but retired after the Southern Song empire had been conquered. Apart from the Xunpu, Chen wrote a biji-style essay called Youzhibian 游志編.

The Xunpu was, according to the preface, written in 1245. It describes the different kinds of mushrooms growing in the area of Taizhou 臺州, Zhejiang, the hometown of Chen Renyu. The rich varieties of mushrooms in the region are mentioned in Ye Mengde's 葉夢得 (1077-1148) Bishu luhua 避暑錄話, and Zhou Mi's 周密 (1232-1298) Guixin zashi 癸辛雜識. The Southern Song court loved the fungi of that region.

In total, there are 11 kinds of mushrooms, namely taixun 臺蕈 (hexun 合蕈), chougao xun 稠膏蕈, likexun 栗殼蕈, songxun 松蕈, zhuxun 竹蕈, maixun 麥蕈, yuxun 玉蕈, huangxun 黃蕈, zixun 紫蕈, siji xun 四季蕈 and egao xun 鵝膏蕈 (identification with scientific names is difficult). The author describes the places where these kinds of mushroom grow, when they are to be harvested, they appearance, and, in an appendix, how to treat persons poisoned by a mushroom.

Although the Xunpu is far from providing a complete overview of all types of mushrooms, it is practically the first treatise of this kind. It is interesting that the detoxication methods described by Chen Renyu differ from those described by much earlier books like Zhang Hua's 張華 Bowuzhi 博物志 and Tao Hongjing's 陶弘景 Bencao zhu 本草注.

|

The Japanese scholar Satō Seiyū 佐藤成裕 (1762-1848) did a lot of research of edible fungi. Apart from his own book, Onkosai Kinbu 温故斎菌譜, he wrote the essay Onkosai Gozuihen 温故斎五瑞篇 (1796), in which (part Keikinroku 驚蕈錄) he quotes from Chen Renyu's Xunpu. Source: 国立国会図書館 / National Diet Library. |

The Xunpu is included in the series Baichuan xuehai 百川學海, Mohai jinhu 墨海金壺, Zhucong bielu 珠叢別錄, Shuofu 說郛, Shanju zazhi 山居雜志, Xianju congshu 仙居叢書, Shoushange congshu 守山閣叢書 and Siku quanshu 四庫全書. Quite interestingly, the local gazetteer (Guangxu) Xianju xian zhi (光緒)仙居縣志 proves that there were versions of the text that included a second preface (xu 序) written by Wang Xusheng 王魏勝 and an afterword (ba 跋) by Hu Yunjia 胡允嘉 (1570-1614). This version also says that the book had an alternative title, namely Xiangcaopu 香草譜.

Japanese scholars were particularly interested in Chinese books on mushrooms. The earliest text on fungi transmitted to Japan was Zhicaotao 芝草圖, which was brought to the archipelago in the late 9th century by Buddhist monks or by diplomats. Chen Renyu's Xunpu was studied by Matsuoka Gentatsu 松岡玄達 in Igansai Kinpin 怡顔斎菌品 (1761), Sō Senshun 曽占春 in Kōwa jinpu 皇和蕈譜 (1791), Sakamoto Kōnen 坂本浩然 in Kinpu 菌譜 (Kōnen Kinbu 浩然菌譜, 1835), and Wu Lin’s Wuxunpu 吳蕈譜 was adapted by Satō Seiyū 佐藤成裕 in his Onkosai Kinbu 温故斎菌譜 (before 1780).

Guangxunpu 廣菌譜 was written during the Ming period 明 (1368-1644) by Pan Zhiheng 潘之恒 from Xin'an 新安 (today part of Xiuning 休寧, Anhui). About his life, not much is known, apart from that he is the author of the books Xin'an shanshui zhi 新安山水志, Genshichao 亙史鈔 and Tianwu zazhi 天吳雜志.

The texts consists mainly of quotations from the mushrooms section of Li Shizhen's 李時珍 (1518-1593) materia medica compendium Bencao gangmu 本草綱目 (ch. Caibu 菜部, sub-chapter Zhi'er lei 芝栭類), but also from other sources. The Guangxunpu is first quoted in Tao Ting's 陶珽 (jinshi degree 1610) collection Shuofu xu 說郛續, which was printed in 1646. As it is not recorded in the bibliographical chapter of the official dynastic history of the Ming dynasty, Mingshi 明史 (96-99 Yiwen zhi 藝文志), from 1645, nor in its 1723 reprint, it appears that Pan's Guangxunpu did not attract much attention. The brief Guangxunpu (or what is preserved of it) is recorded in the agricultural compendium Shoushi tongkao 授時通考 from 1742.

The 20 sections of the Guangxunpu are each dedicated to one particular type of mushroom, but not in a strict scholarly sense. The types muxun 木菌, wumu'er 五木耳, sang'er 桑耳, huai'er 槐耳 and liu'er 柳耳, for instance, are all of the genus mu'er 木耳 (Auricularia spec.). While some species are easy to identify, like tianhua xun 天花蕈 (Pleurotus ostreatus, oyster fungus), yangchang cai 羊肚菜 (Morchella esculenta, morel), xiangxun 香蕈 (Lentinula edodes, shiitake) or jixun 雞蕈 (Cantharellus lateritius), others cannot be identified with their modern scientific names, e.g. guanxun 雚菌, zhuru 竹蓐, zaojiao xun 皂角菌 or duocai 舵菜. Pan's classification is moreover opaque by adding sub-types to types, like the section mogu xun 蘑菰蕈 that is divided into mogu xun and yangchang cai, or guixun 鬼菌, a section consisting of guixun, xiling 地苓, and guibi 鬼筆.

The book Wuxunpu 吳蕈譜 written by Wu Lin 吳林 (fl. 1683), courtesy name Xiyuan 息園 (erroneously called Wu Song 吳崧 or Lin Xiyuan 林息園), from Changzhou 長洲 (today part of Suzhou 蘇州, Jiangsu), has a strong local inclination.

Mushrooms in the region around Suzhou are already mentioned in Wang Ao's 王鏊 Gusuzhi 姑蘇志 from 1506. Statements about fungi in other local gazetteers like Yue Dai's 岳岱 Yangshan jiuzhi 陽山舊志, Niu Ruolin's 牛若麟 Wuxia zhi 吳縣志, Chen Renxi's 陳仁錫 Yangshan zhi 陽山志 or Wu Xiuzhi's 吳秀之 Wuxian zhi 吳縣志 influenced Wu Lin's book on Suzhou mushrooms. The dates of life of Wu Lin are unknown, but the preface dates from 1683.

The Wuxunpu describes 26 kinds of mushrooms divided into three categories of qualities. The best nine types are leijing xun 雷驚蕈 (songhua xun 松花蕈), meishu xun 梅樹蕈, caihua xun 菜花蕈, goushu xun 構樹蕈, chake xun 茶棵蕈, sangshu xun 桑樹蕈, ezi xun 鵝子蕈, maochai xun 茅柴蕈 (hongjian xun 紅襇蕈), and guanxun 館蕈 (songxun 松蕈). Yet the book does not scientifically discern between species. The type leijing has a kind of sub-type called wulei 烏雷, and the ezi mushroom type has some sub-types called fen ezi 粉鵝子, huang ezi 黃鵝子 and hui ezi 灰鵝子, and the sub-type huangjiluan xun 黃雞卵蕈. It is impossible to identify these names with modern nomenclature.

Wu describes the appearance , habitat, seasons, tastes and preparation of mushrooms. He also refers to local collectors' experience which is still useful for modern times. The book ends with some information on poisonous fungi and the medical treatment in case of intoxication.

The book is included in the series Zhaodai congshu 昭代叢書, Ciyantang congshu 賜硯堂叢書 and Nongxue congshu 農學叢書.

The anonymous book Taishang lingbao zhicao pin 太上靈寶芝草品, with a length of 1 juan, belongs to the Daoist canon Daozang 道藏. It is the oldest surviving Chinese book showing illustrations of the mushroom species described. The book belongs to the Lingbao tradition that flourished during the 4th and 5th centuries CE, and is quite probable the origin for the term lingzhi 靈芝 (short for lingbao zhicao 靈寶芝草), used to denote an auspicious type of mushroom whose consumption can lead to immortality.

The preface of the book clearly says that mushrooms could be used as a technique to prolong one's life (yan ming zhi shu 延命之術). The book attempts to elucidate the differences between various species of mushrooms that are notoriously difficult to tell apart from each other (shi nan bian bie 實難辨別). The books therefore presents no less than 103 illustrations, explains appearance, tastes and habitats of the species, and their value for diet and Daoist practice of prolonging life. In this way, the Lingbao book combines Daoist religion with scientific aspects of the biology of mushrooms.

|

|

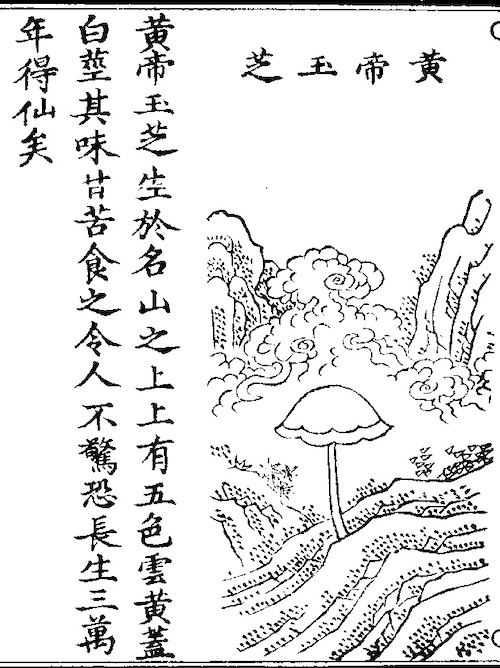

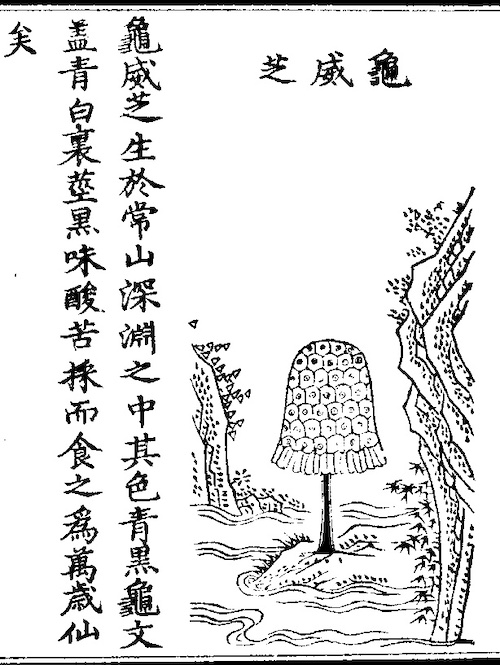

Left: "Jade fungus of the Yellow Emperor" (Huangdi yu zhi 皇帝玉芝), above whose habitats auspicious cold are said to appear. Consumption will liberate man from fear, and even promise a life of 30,000 years of length. Right: "Tortoise fungus" (guiwei zhi 龜威芝), which is found in the vales of Mt. Changshan 常山. The book even shows much more fancier fungi with square umbrellas or such that grow in several storeys and with branches. |

|

Zhong zhicao fa 種芝草法 "Methods of cultivating mushrooms", also called Laozi yuxia zhong zhongzhi jing shenxian bishi 老子玉匣中種芝經神仙秘事 "The Old Master's jade casket containing the scripture on growing cryptograms as a secret of divine immortals", is likewise a text of the Daoist canon. The transmitted text might be identical to the book Mingtongji 冥通記 quoted in Wang Hao's 汪灝 (jinshi degree 1685) Guang qunfangpu 廣群芳譜 (ch. Huipu 卉譜), and might be related to ancient texts on mushrooms mentioned in Wang Chong's 王充 (27-97 CE) Lunheng 論衡 (ch. Chuilin 初稟) and Ge Hong's 葛洪 (283-343 or 363) Baopuzi 抱樸子 (ch. Huangbai 黃白篇). The bibliographical chapter Jingji zhi 經籍志 in the dynastic history Suishu 隋書 lists a book called Zhongshenzhi 種神芝, which likewise might be the Daozang text. In the Daoist canon, the book has mainly the function of detailing ceremonies around the consumption of mushrooms. Yet is is also quoted in Chen Haozi's 陳淏子 (b. c. 1612) scientific book Huajing 花鏡.

Apart from the book described above, quite a few books on edible mushrooms are lost:

| title, size | author | mentioned or listed in | |

| 黃帝雜子芝菌 十八卷 | Huangdi zazi zhixun | 漢書·藝文志 | |

| 木芝圖 一卷 | Muzhi tu | 抱樸子內篇·遐覽篇, 仙藥篇 | |

| 菌芝圖 一卷 | Xunzhi tu | idem | |

| 肉芝圖 一卷 | Rouzhi tu | idem | |

| 石芝圖 一卷 | Shizhi tu | idem | |

| 大魄雜芝圖 一卷 | Dapo zazhi tu | idem | |

| 靈芝瑞草象 一卷 (靈芝瑞草圖; 神仙芝草圖 二卷) | Lingzhi ruicao xiang (Lingzhi ruicao tu; Shenxian zhicao tu) | (Jin) 陸修靖 Lu Xiujng (?) | 浙江通志, 湖州府志, 讀書敏求記 |

| 芝草圖 一卷 | Zhicaotu | 隋書·經籍志, 舊唐書·經籍志, 新唐書·藝文志, 本草經集注 | |

| 種芝經 九卷 | Zhongzhijing | 舊唐書·經籍志, 新唐書·藝文志 | |

| 神仙玉芝瑞草圖 一卷 | Shenxian yuzhi ruicao tu | (Jin) 陶宏景 Tao Hongjing (?) | 宋史·藝文志 |

| 靈芝記 五卷 | Linzhiji | () 穆修靖 Mu Xiujing | 宋史·藝文志, 通志·藝文略, 本草綱目·序例 |

| 芝草圖 三十卷 | Zhicaotu | (Tang) 孫思邈 Sun Simiao | 宋史·藝文志 |

| 靈寶服食五芝精 一卷 | Lingbao fushi wuzhi jing | idem | |

| 餌芝草黃精經 一卷 | Erzhicao guangjing jing | idem | |

| 朝元子玉芝書 | Chaoyuanzi yuzhi shu | () 陳君舉 Chen Junju | |

| 符瑞記 | Furuiji | (Sui) 許善心 Xu Shanxin | |

| 瑞應圖記 | Ruiying tuji | (Liang) 孫柔之 Sun Rouzhi | |

| 神仙服食藥方 | Shenxian fushi yaofang | (Jin) 抱樸子 Baopuzi | |

| 神仙服食方 | Shenxian fushi fang | (Jin) 抱樸子 Baopuzi |