The qieyin 切音 alphabets were the first attempts at creating a phonetic transcription of the Chinese script. These transcription systems were pathbreaking for the development of the Zhuyin alphabet 注音字母 developed during the 1920s.

Traditionally, the pronunciation of Chinese characters was indicated by the fanqie system 反切. The initial sound and the final sound of a word were represented by two other characters, like the [d-] of 德 [də] and the [-ʊŋ] of 紅 [hʊŋ] for the pronunciaton [dʊŋ] of the character 東. This approach still played a part in the creation of the qieyin alphabets as well as of the Zhuyin alphabet.

The intention of creating such alphabets was to raise literacy and to lift up the general standard of eduction, which could eventually contribute to a growing independence and strength of the Chinese nation. Texts written in Chinese characters and accompanied by a phonetic system could be read without consulting character dictionaries. Furthermore, easy-to-learn phonetic symbols could be used to replace characters and to express oneself in written form without relying on complicated characters. This method was compared with the Japanese syllabic scripts Katakana and Hiragana which are used besides the Chinese characters and are used to indicate the pronuncation of characters.

The different attempts at creating a phonetic alphabet for Chinese made use of the letters of the Latin alphabet, abbreviated Chinese characters, parts of characters, archaic forms of characters or shorthand characters. The most widespread of these transcription systems is Wang Zhao's 王照 (1859-1933) Mandarin alphabet (guanhua hesheng zimu 官話合聲字母) for the idom of Beijing. Yet the forerunner of these scholars was Song Shu 宋恕. In 1891 he wrote an essay called Liuzhai beiyi 六齋俾議 stressing the need of an advanced phonetic system to be used in schools, especially in southern China. The first alphabet was created by Lu Gangzhang 盧戇章 (1854-1928). In 1892 he published his book Yimu liaoran chujie 一目了然初階, in which he presented an alphabet consisting of original and altered Latin letters. It was to be used for the transcription of the idiom of Xiamen 廈門 and could also be used for the dialects of Quanzhou 泉州 and Zhangzhou 漳州. This publication was the starting point of a flood of books presenting transcription systems presented in the following table.

| year | inventor | idioms | name of alphabet or book | type of letters |

| 1892 | Lu Gangzhang 盧戇章 | Xiamen, Quanzhou, Zhangzhou | Yimu liaoran chujie 一目了然初階 | Latin |

| 1895 | Wu Jingheng 吳敬恆 | Wuxi | Douya zimu 豆芽字母 (also called Dengyun jianma 等韻簡碼) | seal and chancery scripts |

| 1896 | Cai Xiyong 蔡錫勇 | Beijing | Zhuanyin kuaizi 傳音快字 | shorthand |

| 1896 | Li Jiesan 力捷三 | Fuzhou | Minqiang kuaizi 閩腔快字 | shorthand |

| 1896 | Shen Xue 沈學 | Suzhou | Shengshi yuanyin 盛世元音 | shorthand |

| 1897 | Wang Bingyao 王炳耀 | Guangzhou | Pinyin zipu 拼音字譜 | shorthand |

| 1901 | Wang Zhao 王照 | Beijing | Guanhua zimu 官話字母 | brush strokes |

| 1901 | Tian Tingjun 田廷俊 | Hubei | Shumu daizi jue 數目代字訣 | Chinese numbers |

| 1902 | Li Jiesan 力捷三 | Beijing | Wushi zitong qieyin guanhua zishu 無師自通切音官話字書 | shorthand |

| 1903 | Chen Qiu 陳虬 | Wenzhou | Xinzi ouwen qiyin duo 新字甌文七音鐸, Ouwen yinhui 甌文音匯 | archaic script 蝌蚪文 |

| 1904 | Li Yuanxun 李元勳 | Daishengshu 代聲術 | brush strokes | |

| 1904 | Liu Mengyang 劉孟揚 | Beijing | Tianlaihen 天籟痕 | brush strokes |

| 1905 | Yang Qiong 楊瓊, Li Wenzhi 李文治 | Xingshengtong 形聲通 | brush strokes | |

| 1906 | Lao Naoxuan 勞乃宣 | Nanjing, Suzhou | Zengding hesheng jianzi pu 增訂合聲簡字譜 | brush strokes |

| 1906 | Lu Gangzhang 盧戇章 | Beijing | Zhongguo zimu Beijing qieyin jiaokeshu 中國字母北京切音教科書 | brush strokes |

| 1906 | Lu Gangzhang 盧戇章 | Fuzhou, Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Xiamen and Guangdong | Zhongguo zimu Beijing qieyin heding 中國字母北京切音合訂 | brush strokes |

| 1906 | Zhu Wenxiong 朱文熊 | Suzhou | Jiangsu xin zimu 江蘇新字母 | Latin |

| 1906 | Tian Tingjun 田廷俊 | Hubei | Pinyin diaizi jue 拼音代字訣, Zhengyin xinfa 正音新法 | brush strokes |

| 1906 | Shen Shaohe 沈韶和 | Suzhou ? | Xinbian jianzi tebie keben 新編簡字特别課本 | Suzhou market numbers 蘇州碼子 |

| 1907 | Lao Naoxuan 勞乃宣 | Fujian, Guangdong | Jianzi quanpu 簡字全譜, Jingyin jianzi shulüe 京音簡字述略, Jianzi conglu 簡字叢錄 | |

| 1908 | Jiang Kanghu 江亢虎 | Beijing | Tongzi 通字 | Latin |

| 1908 | Zhang Bingling 章炳麟 | Niuwen 紐文, chapter Yunwen 韻文 | archaic characters | |

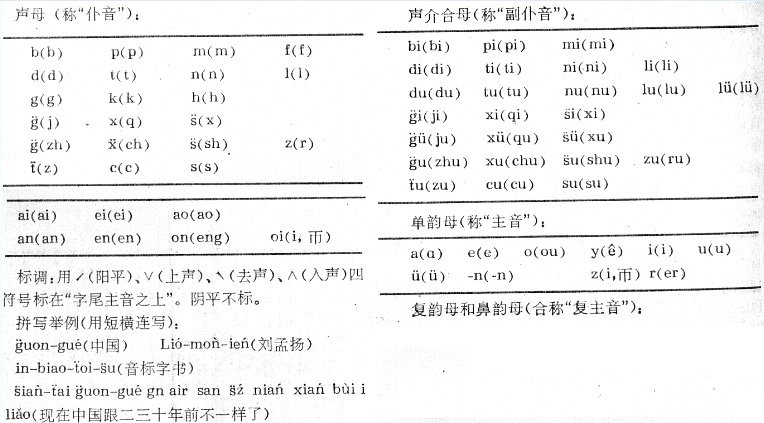

| 1908 | Liu Mengyang 劉孟揚 | Beijing | Zhonggu yinbiao zishu 中國音標字書 | Latin |

| 1908 | Ma Tigan 馬體乾 | Beijing | Chuanyin zibiao 串音字標 | brush strokes |

| 1909 | Song Shu 宋恕 | Wenzhou | Song Pingzi xinzi 宋平子新字 | Japanese kana, abbreviated characters |

| 1909 | Huang Xubai 黃虛白 | Beijing | Hanzi yinhe shizi fa 漢字音和識字法 | brush strokes |

| 1909 | Huang Xubai 黃虛白 | Beijing | Ladingwen yijie 拉丁文臆解 | Latin |

| 1909 | Liu Shi'en 劉世恩 | Beijing | Yinyun jihao 音韻記號 | |

| 1910 | Zheng Donghu 鄭東湖 | Qieyinzi shuomingshu 切音字說明書 | brush strokes |

Although most of these alphabets made use of archaic characters, abbreviated characters and brush strokes as parts of characters (which was, of course, the influence of the Japanese kana alphabets), many others stressed that China needed an alphabet based on the internationally much more important Latin alphabet. While the first alphabets had been made for dialects or topolects, many later alphabets tried to create an alphabet for the language of Beijing as the standard language of the capital. Mandarin (guanhua) was not yet declared the national standard language, but these attempts already demonstrated the need for a standard language that had to be used nation-wide.

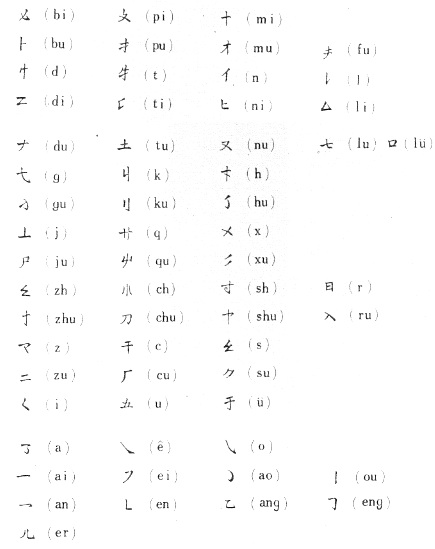

Wang Zhao's alphabet from 1901 shows clearly the influence of the kana syllable alphabets. Yet for the syllable endings, more symbols had to be created. In Japanese, there is only one vowel per syllable, yet in Chinese there are many diphtongs, and also some consonant endings. The four tone pitches were expressed by dots in the corners of the transcription. Like in the later Zhuyin alphabet, the transcription was written to the right side of the characters. It can be seen that the symbols were abbreviated characters, like 必 for [bi], 特 for [tə], or 木 for mu [mu], 夫 for [fu].

|

Liu Mengyang's alphabet used the Latin letters. For sounds not known in Western languages, he made diacritic marks. The letters were used to transcribe different sounds than in the modern Hanyu pinyin system 漢語拼音.

|

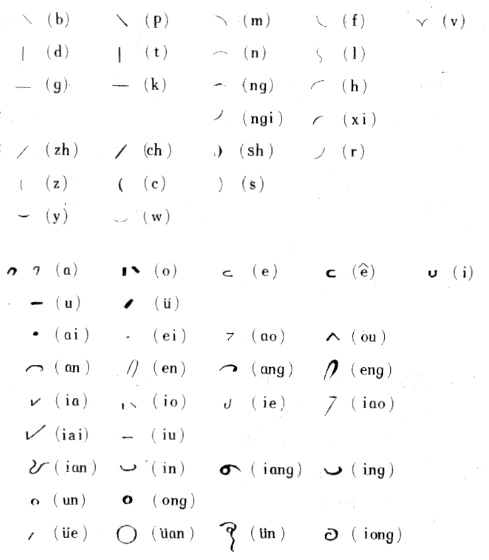

Cai Xiyong used Western shorthand symbols for his alphabet. This was, compared to the other methods, the simplest one, yet for both Chinese and Westerners shorthand is a foreign transcription system that first had to be learned by both sides and was therefore not very attractive.

|

The most widespread transcription systems were those of Wang Zhao and Lao Naixuan. Although both systems attracted the interest of scholars and were used in a large number of textbooks for elementary schools, Wang Zhao's guanhua zimu system was prohibited in 1910. Two years later, with the foundation of the Republic, new attempts were made at creating a transcription system for a standardized national language. The result was to be the Zhuyin alphabet.